Edouard François

For the third consecutive year, Archinov and the CSTB, in partnership with Le Moniteur, the French magazine on construction, organized a “Carte blanche” conference at the Architect@Work show. The guest speaker this year was the architect Édouard François as part of a “renovation” cycle.

Is architecture a bona fide discipline? Some attendees at Édouard François’s talk had their doubts. “What’s behind this flippancy and your taste for provocation?” one of them asked. “Deep despair!” he replied, laughing. Isn’t the building in Paris’ 17th district, decorated with large Ductal flower pots, just another joke? And the Champigny-sur-Marne housing units, a utopia that should never have been seriously considered?

“I’m a contextual architect,” Edouard François likes to repeat. The town of Champigny-sur-Marne has a mix of detached houses, apartment blocks and bourgeois homes. It is a typical suburban area where the desire to differentiate local architecture seems legitimate: “They called me in to create a city center. They asked me to make it pretty. But it made no sense to make this place beautiful. It would have seemed out of place,” he argued. “There’s some serious revisionism going on here: no one wants to remember the 1970s.” From the local setting to the concept, the architect created a kind of chaotic accumulation by reusing and superimposing three archetypes of local buildings. No linkage, no intertwining, just vocabulary, somehow without grammar. The posture is unique, but the whole gives the sense that a city center is now possible: the impressive houses in the lower part of town invite sociability; the housing blocks give the impression of density and the detached houses in the higher part of town lend credence to the effects of the previous two typologies.

Contextual material

Another setting, but the same approach at the intersection of the Champs-Élysées and Avenue Georges V in Paris, where Edouard François used an artful cut-and-paste concept for Hotel Le Fouquet’s. He unified seven existing buildings in an idiosyncratic reproduction of the only authentic Haussmann-style facade on the block, repeating it several times. The commissioned work was an opportunity to test his new “moulé-troué” (cast and punctured) design: a willful mismatch between the imitation Haussmannian facade grey stone moldings and the position of the actual window/door openings, which depend strictly on the interior design. “I don’t work on form,” explains the architect. Recombining the figures of local heritage is part of his experimentation: “I’m looking for confrontations between materials. Working with models is therefore crucial. Color drawings don’t work because the material is more sensual. It’s by trying out materials in a model that you can see whether things converge and alchemy can take place at a site.” Édouard François is also a proponent of low-tech. Raw interiors and facades clad with wood slat fencing in Louviers, gabion walls and camouflage netting for ventilation systems in Chartres, glazing sealed by hand with silicone, and wallpaper with photos of bricks in Clichy, to name a few: there are no limits to the materials that go into his combinations. “We make people live between four plaster walls but we’ll end up driving them crazy because that’s not what they want. They want toile de Jouy, exposed cinder block and a hodgepodge of bricks!”

“Green” is not anti-contextual

Édouard François is often called a “green” architect, probably because of the pervasiveness of plant material in some of his works. “But I’ve always used vegetation in a contextual way,” he points out. “And I refused to design the plant facade suggested to me for Hotel Le Fouquet’s, located in the Golden Triangle – the most chic part of Paris.”

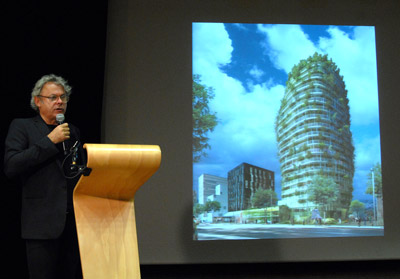

Without betraying his convictions, the architect has ventured into a project to build a tower that breaches the Parisian regulatory ceiling. A 50-meter building named Tower of Biodiversity. Sensitive about the height, he says, “The skyline is politically correct, but this project will really help bring biodiversity into the capital.” Covered with wild plants collected by the Du Breuil School, “the tower will seed its territory by the action of the winds.” To do this, “some plants will be grown in tubes 50 cm in diameter and 3.50 meters long. The idea required two years of tests on species of chasmophytes, known for their ability to grow in crevices,” enthuses the architect, who graduated from the École nationale des ponts et Chaussées and the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts.

With an accent on the social as well as the ecological, two other towers by Édouard François should soon grace the Bonne urban development zone (ZAC) in Grenoble. One of them will have large roof terraces. “Clearly, we’re making apartments that are too small. An average 60 m² is inadequate for decent housing. People are losing any kind of sociability. So, how do you give the impression of living on 200 m²?” asks Édouard François. He thinks one solution is to dissociate the balconies of the housing units by stacking them on the roof. “It’s by spreading out that you can do something.” In Grenoble, “these 35-m² outdoor spaces will be additional rooms under the sky that will enable people to welcome friends without disturbing the privacy of the apartment.” An elevator will take you there, and they will have separate entrances, summer kitchens and bathroom facilities. “Do people really go up there?” a conference attendee asked. “It works amazingly well!” Édouard François answers without hesitation, convinced by a number of experiments in Panama and Canada. In any case, “architecture doesn’t work without a good measure of dreaming.” The true test will come when the project is completed in 2015.

Learn more: