A close look at smells

How to "measure the impossible"? This was the challenge that the European commission set down in a call for proposals in experimental research with 15 different themes. The program included the role of sound in the design of objects, the measurement of pleasure procured through video games, consciousness mechanisms. And also, perceived air quality measurements. CSTB and nine other technical European experts started this adventure with two objectives, firstly to fully understand the perception of odours through their similarities and differences, and secondly to develop new sensors to measure smells. The purpose? To help control air quality in buildings and vehicles, but also to assist material evaluation protocols and even quality control during production. Experts presented their report in August 2009, after three years of work. A new look at the work that explores the inexplorable.

Smell and feel

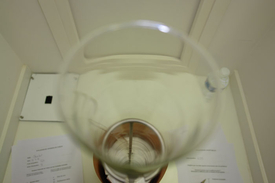

It all began in Sweden. About thirty materials were smelled in pairs by blind volunteers and marked (from 0 to 10) as a function of their similarity or dissimialrity. Did the carpet smell like linoleum ? Is the smell of paint diametrically opposite from the smell of old paper? And to what extent? A total of 870 combinations were assessed. "It was thus possible to draw up an odour map, something like a colour chart, says Olivier Ramalho, CSTB research engineer. This is a major finding. The final classification of odours was approximately the same found for different persons, although everyone used his or her own personal parameters to achieve this classification." 12 reference odours were thus identified to act as parangons for a category of smells.

At the same time these tests were being carried out, the researchers from CSTB – and their peers in Germany – have analyzed several construction materials in order to identify the odour-active molecules. This close examination revealed that these molecules originated mostly either from the ageing of the natural material (linen, wood, jute) used in some of the building product, or from the degradation of synthetic polymers in the others.

A promising beginning

All these laboratory results proved to be valuable to design a sensor system that is able to mimic human olfaction. This full scale system still had to be tested and compared with the perception from our real nose. CSTB workers were ready to enter the fray, by offering their noses for a test organised on the site of Champs sur Marne. A comparative study was also carried out at Renault, one of the project partners, inside a Scenic and a Clio car. Was the sensor system as sensitive as a real nose? It was the challenge undergone through a series of tests. The result? "The system still needs to be adjusted, overall in terms of sensitivity to odour intensity and air humidity management, says Olivier Ramalho. There is still a lot of progress to be made. But this multi-disciplinary cooperative work that brought together chemists, psychologists and sensor manufacturers was very fruitful. And we successfully obtained the first version of a stable odour space applied to materials." Another benefit of this large European study is that we achieved a better knowledge of odorous compounds that emphasises the major role of the presence of natural components in materials in the occurrence and development of smell. In summary, it has been a first experience full of promise for the years to come.